Kiawah Settles with Cyclist

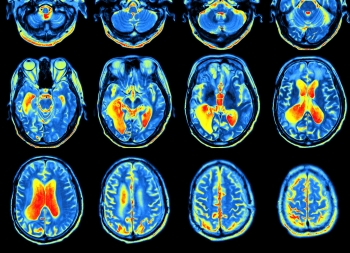

Lawsuit focused on brain injury’s economic impact

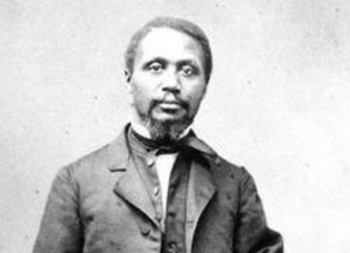

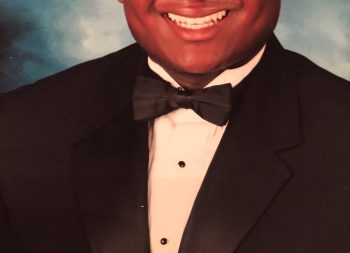

Former competitive cyclist Christopher Cox had a promising career as a Wall Street analyst before his life took a sudden turn four years ago during a leisurely bike ride on the beach at Kiawah Island.

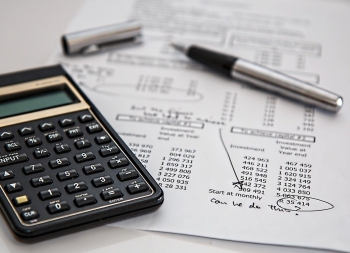

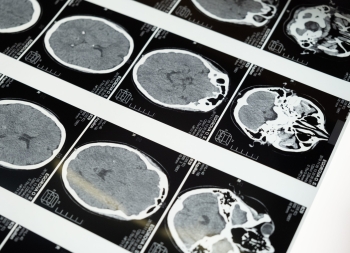

While on vacation in May 1997, Cox was injured when the front fork of a bicycle he had rented snapped, sending him crashing to the sand. Cox’s visible injury was a broken right collarbone. But it was unseen brain damage that led to a lawsuit against Kiawah Island Golf & Tennis Resort and other defendants who recently settled for $1.75 million.

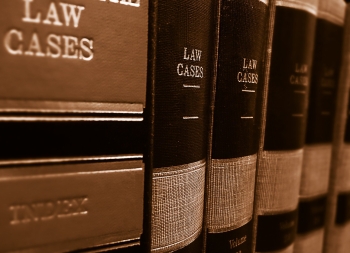

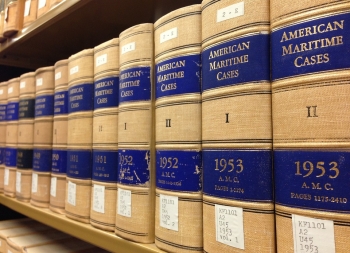

The settlement was the largest brain-damage award in South Carolina, said Stephen Smith, a Hampton, Va., attorney who specializes in brain-injury cases around the country. Legal claims for brain injuries are often included in lawsuits filed as a result of accidents that also cause other physical injuries. But Cox’s lawsuit is unusual, legal experts said, because he sued for a brain injury alone.

Similar lawsuits may begin showing up around the country because doctors, armed with more medical knowledge, are better able to diagnose brain injuries that once went unnoticed, said Jacksonville attorney Dianne Weaver, who serves on the board of the National Brain Injury Association in Washington.

In his lawsuit, Cox alleged that because of his brain injury he can no longer function in the high-pressure world of buying and selling stocks, and he lost the ability to do multiple tasks at the same time. Cox suffered a mild brain injury, but that can be more devastating than a physical injury, Smith said.

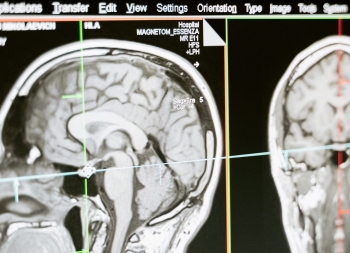

Cox, 32, said that when he fell he was knocked unconscious for about 15 minutes. When he woke up, Cox said, he did not know he was at Kiawah or that he had recently earned a master’s degree in business administration from Harvard University. Since the accident, Cox said, he struggles with a loss of short-term memory. Even now, Cox said, he does not remember the accident on May 4, 1997.

Defense attorney Steve Darling of Charleston said the company’s decision in January to pay Cox is not an admission that Kiawah couldn’t have won if it had gone to trial. The settlement, Darling said, was a compromise to avoid the uncertainty of what a jury might have awarded. “It is far less than what they initially demanded,” he said.

But the lawsuit, filed in 1999, did not ask for a specific amount of money, Smith said. “If they didn’t think the case had some value, then why did they pay almost $2 million?” Smith asked. “The moneyprovides my client with economic security, but there is no amount of money that can compensate one for being the survivor of a traumatic brain injury.”

Charleston attorney Richard Rosen, who also represented Cox, said Kiawah settled the case because it lost the evidence – the bike Cox was riding. “They had control over the bicycles and the maintenance records. A couple of years later, everything disappeared. There was evidence the bike was defectively rusty and that would have worked to our advantage.”

Cox, a New York City native, was a winning high school cyclist. The son of a banker, Cox had lived in Tokyo and London and on both coasts of the United States. He had considered trying out for the U.S. Olympic cycling team, a decision that would have interfered with college, he said. He earned a master’s degree in international relations from Cambridge University in England. After working as the chief executive officer of a bicycle company in upstate New York, he got a Harvard MBA. He and a Harvard classmate vacationed at Kiawah to celebrate. That’s when the bike accident changed his life.

In the first two years after Harvard, a Wall Street mutual fund paid Cox a six-figure salary to manage more than a $1 billion in investments. But Cox said that after the accident, he was not the same person he was before it. By the end of his second year, Cox said he left Wall Street because of a change in his mental abilities. He was afraid, he said, of making a mistake. He’s enrolled in the exercise science program at the University of South Carolina.

When Cox fell, Smith said he suffered a concussion, which tore the interconnecting microscopic fibers that chemically carry information through the brain. These fibers are called axons. Cox experienced axonal shearing, Smith said. Smith said Cox is not disabled or mentally retarded and the brain injury does not affect his IQ. But it does affect his ability to access what he has learned. “He was going to be one of the lions of Wall Street, but he will never achieve his potential,” Smith said.

Cox was not wearing a helmet, and the resort did not provide one, Smith said. While it is always best to wear a helmet while riding a bicycle, Smith said a helmet did not appear necessary during Cox’s casual ride at the beach on a one-speed bike. Brain injuries are a silent epidemic nationwide, said William Winslade, a professor at the University of Houston Law Center. Between 50,000 to 60,000 people die annually from brain injuries suffered as a result of sports and traffic accidents, falls and gunshot wounds, he said.

The majority of brain injury victims do not lose consciousness, Smith said. Whiplash from a rear-end car collision can cause axonal shearing, he said. “You don’t even have to strike your head to have a brain injury,” he said. Like Cox, the majority of brain-injury victims adapt to different lifestyles, he said.

The company, Cox said, argued that if he is not mentally retarded, then what has he lost? Speaking metaphorically, Cox said while he might never be a competitive cyclist again, he can still ride a bike. While he’s able to work, Cox said he will never earn as much as he could on Wall Street. That realization, he said, is sometimes disappointing. “But if you can separate the financial happiness and being happy at what you are doing, it shouldn’t cause a big impact. But I don’t know. I haven’t done it yet.”

BY: Herb Frazier

The Post and Courier