The Corporate Check-in – Spring Cleaning

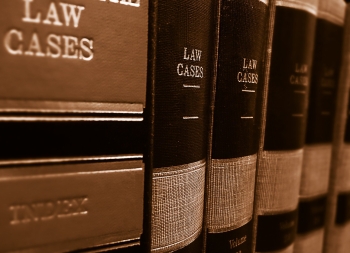

The late Anthony Bourdain once said that “If anything is good for pounding humility into you permanently, it’s the restaurant business.” It’s also good, perhaps, for pounding into you the incredible importance of observing all the corporate formalities required by the state of South Carolina, thanks to the recent South Carolina Supreme Court case of Pertuis vs. Front Roe Restaurants, Inc.

Many of the details in the Pertuis case are inconsequential. What is consequential is that an unclear agreement concerning corporate ownership percentages led to three separate legal proceedings that lasted years and resulted in legal bills, distraction, and presumably ill will. All of which could have been avoided with a little help from a corporate attorney knowledgeable in South Carolina law.

The story, in very broad strokes, is this: Mark and Larkin Hammond built and operated several successful restaurants in Lake Lure, North Carolina, and Greenville, South Carolina. The Hammonds hired Kyle Pertuis to manage the restaurants, and as part of his compensation, Pertuis acquired minority ownership interests in the three restaurants—Lake Point (NC), Beachfront (NC), and Front Roe (SC) respectively. His interest was tied to either time spent working for the Hammonds, who had created several corporations, or the financial performance of one of the restaurants. Pertuis eventually decided to leave the business, and a dispute arose concerning the percentage and valuation of his ownership interests in the three restaurants.

In the end, after a trial and an appeal, the South Carolina Supreme Court reviewed the whole history of the dispute and found that, despite an argument that the separate corporations should have been treated as one business entity, they weren’t, and Mr. Pertuis was not entitled to the award the trial court had given him – a 10% share of the business, with a value of around $100,000. Instead, he walked away with just over $27,000, which may have just covered his legal fees.

Of the Supreme Court’s opinion, this is arguably the most important part for our purposes: Pertuis testified that, as to the vesting schedule for his interest in Front Roe, Pertuis’s ownership interest was based on certain unidentified profit margin goals; Pertuis explained, “There was an initial letter similar to form of this [sic] around a creative way to structure something. … It had a proposed way to do things going forward that we were going to solidify at a later date.” However, Pertuis stated on direct examination:

Q. And at any time did you have any clear understanding about what it was going to take for you to be vested in an increased amount of ownership in the River [restaurant operated by Front Roe]?

A. No, I didn’t have clarity on that other than that original document that was put together just kind of saying, hey, this is how we will structure [vesting.]

Translated into everyday English, what these statements mean is that the fundamental agreement spelling out what Kyle Petruis was entitled to was not clear, was not written down, and at best was “something that was going to be solidified at a later date.”

Two observations about this. First, this is not an uncommon situation. In fact, it’s not even the exception – it’s basically the rule. Particularly with small businesses and time-pressed owners who have very long to-do lists, the details of the corporate structure that underlies everything don’t seem important. They’ll get to it later. But later never arrives, and at some point, this grey area becomes a problem. It could be a change of ownership, a lawsuit, or the departure of a key employee. But sooner or later, it always becomes a problem. Always.

In addition, in the absence of these agreements, there is law in effect that will allow judges and courts to determine, based on the circumstances, whether a group of corporations should be treated as one big company. Known as the “single business enterprise theory”, the concept is that when business entities are being created and used to circumvent the law and, as the court put it, defeat justice, groups of corporations can be treated as if they’re one big company. It’s not an easy argument to prove, but it can be done, and Mr. Petruis came fairly close.

Second, this problem is exactly what corporate attorneys can help a client prevent. A huge part of our job is to structure agreements, documents, and formalities every business depends on to make sure they’re clear, legal, and binding. And if these things are missing, or have been improperly used, we are also quite capable of litigating the issue.

A regular check-in with a corporate attorney about the legal status of your business is a good idea and can save you time and money in the long run. Laws change. Situations change. Corporate documents may need to be updated and corrected, or, depending on which side you are on, you may have grounds for a lawsuit. Either way, it pays to consult with an attorney and to keep up with formalities. Failing to keep up can, as Mr. Petruis learned, be a very expensive mistake.