Email Tracking and Attorney-Client Relationship: Wait And See.

One of the most consistently interesting areas for any attorney is the intersection of technology and law, particularly when the technology is widespread. A perfect, fascinating example of this is email, perhaps the world’s most widely used technology. As more and more people send more and more emails, the law struggles to keep up.

According to one source, about 124.5 billion business emails and 111.1 billion consumer emails are sent and received each day in the US alone. Today, technology is available to track whether those emails were received, read and/or forwarded, and can even track what device was used by the reader. When this occurs in the context of litigation, an increasingly significant question is whether this technology violates confidentiality, or other ethical guidelines. For example, what if this technology is employed by an attorney and ultimately reveals the identity of an undisclosed consultant?

As is so often the answer in complex legal situations, the answer is “It depends.” There are only two state bar ethics opinions dealing specifically with this question, one from New York, and one from Alaska, fifteen years apart. And boy, are they unhelpful, particularly when taken together.

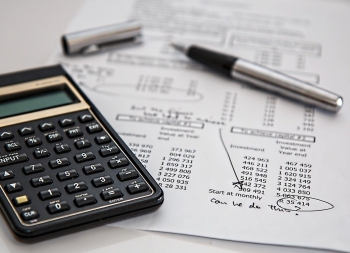

Superficially, the New York opinion seems to forbid email tracking technology. However, the opinion, delivered in 2001, first conflates tracking technology with metadata analysis. Metadata is information in a document that’s normally not visible, but can be uncovered by a knowledgeable user and reveals revisions, comments and other editorial information that can be related to legal strategy, thought processes and other information that’s clearly privileged. While email tracking could conceivably reveal privileged information (when information is forwarded to an expert consultant, for example), it generally does not give the sender enough editorial information to raise privilege concerns.

The other problem with the New York opinion is that when it was written, technology for detecting the presence of tracking code in inbound emails was either nonexistent, or severely limited. Now, eighteen years later, there are numerous software packages that can scan inbound emails for tracking, and alert recipients. The technological playing field has been leveled.

Interestingly, the Alaska opinion arrives at the same conclusion, but through strikingly different reasoning. First, the Alaska committee found that attorneys can assume that emails they receive will not be tracked, which connects the ethics of a technology with its prevalence. Given that there are dozens of email tracking technologies on the market, this conclusion seems misguided based on its own reasoning. Second, the Alaska opinion seems to condemn the use of tracking as an attempt to “invade the attorney-client relationship” and in so doing, introduces an element of intent regardless of whether the receiving attorney knew of the tracking or not. This logic seems to contradict the increasing importance of Model Rule 1.1, which creates an ethical obligation for attorneys to be abreast of the risks and benefits associated with technology. In other words, lawyers are expected to understand how technology works, and how it can affect their clients. In practice, that can be read to mean they’re responsible for detection of tracking technology in inbound emails.

Which leads us right back to where we began – with a rapidly evolving technology, a legal framework that lags behind, and guidance that is both unclear and occasionally contradictory, to say the least. And this, by the way, is before we even begin to analyze federal law, which was created for an entirely different category of technology (pen registers, trap and trace devices, and computer hacking and fraud) but refers to it as well. And in the meantime, until the people who write the laws catch up with the people who write the code, the best conclusion we can arrive at is: let’s wait and see.